Loss Aversion: Why Flybondi No Longer Holds the Second Place in the Argentine Market (and How to Reclaim It)

When the threshold of perceived risk outweighs the potential benefit of savings, price ceases to be the deciding factor. Nearly 50 years ago, two psychologists explained how and why we make the decisions we do: the fear of losing is always greater than the desire to win.

Every purchase of an airline ticket is an exercise in psychological calculation. On one hand, there's the tangible promise of a low price, a saving that feels like an immediate gain. On the other hand, the intangible shadow of uncertainty: the fear of cancellation, of delay, of the entire plan falling apart.

JetSMART launched a campaign in Argentina, differentiating itself from the other low-cost carrier in the domestic market, Flybondi, by (not so) elliptically attacking the great weakness of the former second power in Argentine domestic aviation.

For years, in the Argentine market, a low fare was a dominant argument. But in the 2024-2025 period, we witnessed a massive real-time experiment that proved that when reliability falls below a critical threshold, the psychological balance tips decisively and almost irreversibly.

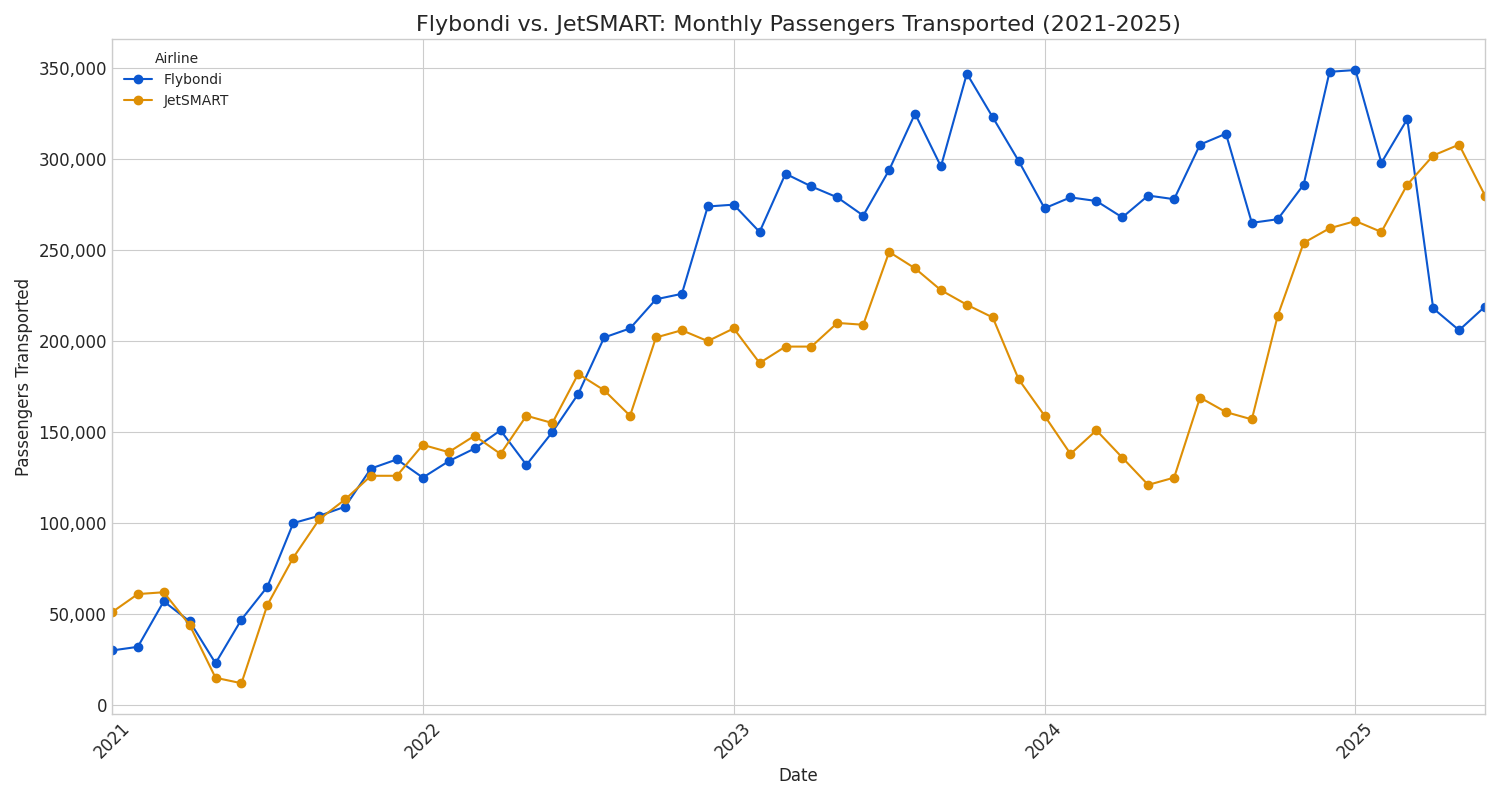

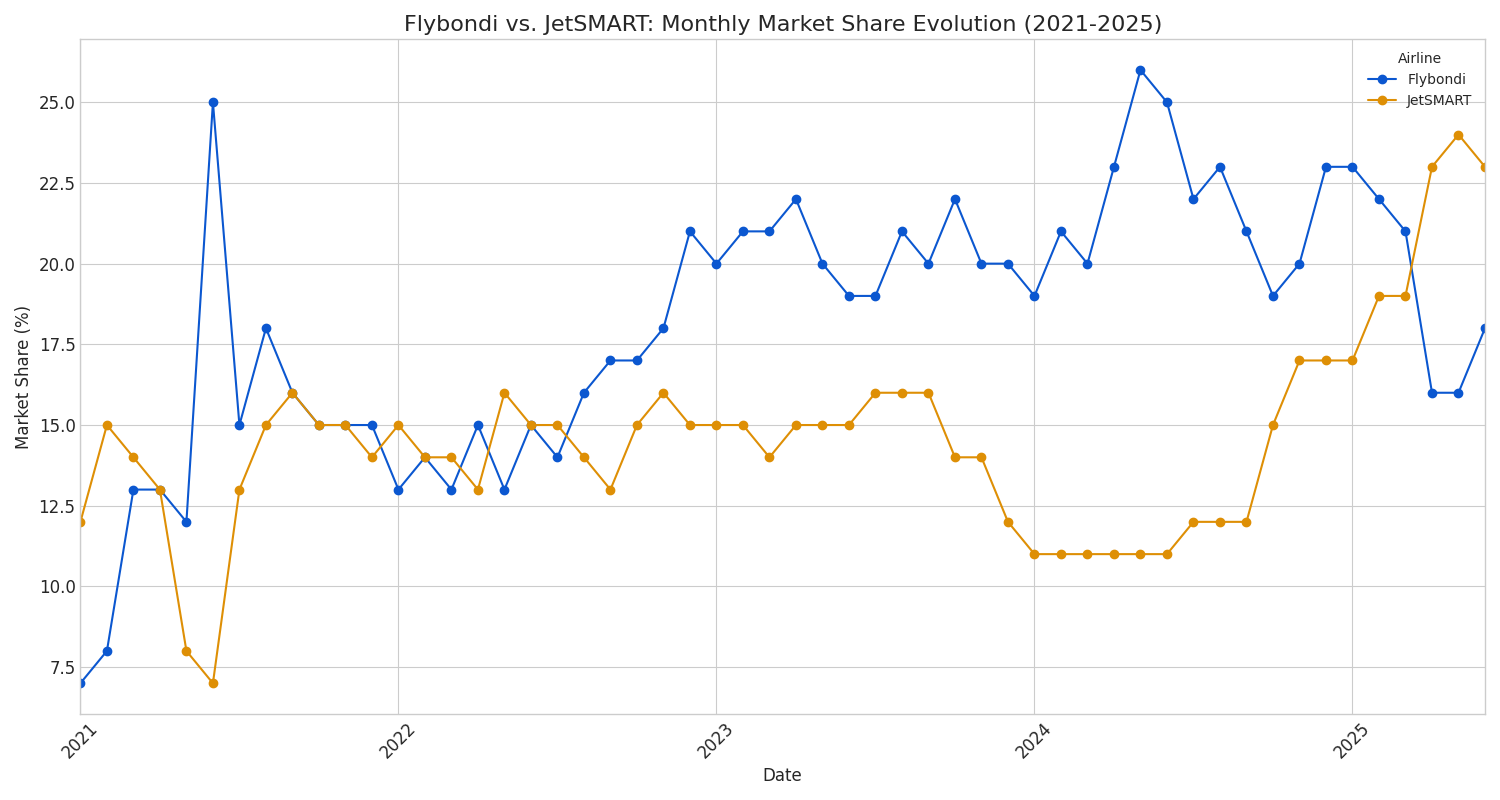

The collapse of Flybondi's market share and the simultaneous rise of JetSMART isn't just a simple story of corporate competition: it's a lesson on the power of Loss Aversion, the fundamental principle demonstrating that in the human mind, the fear of losing will always be stronger than the desire to win.

The Unbearable Pain of Losing

To understand the dynamics of the airline market (or any other), one must first understand the architecture of human decision-making. Economists and psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for "having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty."

In 1979, Kahneman and Tversky demolished the idea of the purely rational consumer with their Prospect Theory. Of their work, the most potent postulate is Loss Aversion. In their own words, "losses loom larger than gains," and research has appropriately quantified this asymmetry: "the pain of a loss is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of an equivalent gain."

Let's apply this principle to the traveler's dilemma:

The "Gain": The money saved by buying a ticket on the cheaper airline.

The Potential "Loss": A canceled flight. This is not a simple inconvenience; it is an accumulation of catastrophic losses: the cost of a non-refundable hotel, a crucial business meeting missed, a ruined family vacation, and the stress and exorbitant expense of buying a last-minute replacement flight.

Because the pain of these potential losses is psychologically overwhelming, the consumer is willing to pay more to avoid them. That premium paid for a ticket on a more reliable airline is not an expense; it is a risk premium: a fee consciously paid to insure against catastrophe.

The Argentine Laboratory

The post-pandemic Argentine market became the perfect laboratory to test this theory. The air transport liberalization that began in 2016 fostered competition, with Flybondi pioneering the ultra-low-price model and JetSMART entering with a modern fleet. However, these airlines operated under a condition of chronic stress.

Currency controls and difficulties in accessing foreign currency have been a persistent feature of the Argentine economy, with severe crisis peaks during 2022 and 2023. This was not a sudden storm; it was a constant high tide testing the resilience of each business model.

Flybondi's strategy, based on a fleet of Boeing 737-800s with an average age of 15 years, represented a gamble. It accepted higher maintenance costs in exchange for lower capital costs. Under the chronic pressure of the currency crisis, this gamble failed. The difficulty in importing spare parts disproportionately hit its higher-need fleet.

This difficulty, repeatedly voiced by the company, clashed with two realities: one, the inability to develop alternative supply strategies and financial circuits, and the other, JetSMART's competitive advantage of having its central maintenance and administrative hub in Chile. This allows it to rotate equipment and have spare parts and consumables available for its checks and unscheduled maintenance, isolating it from the local situation.

This detail, added to the demonstrably lower wear and tear and maintenance needs of a new fleet of aircraft, resulted in a higher utilization rate and a much-reduced Aircraft on Ground (AOG) time compared to Flybondi's. The combination of the latter's expansion of its route network and seat offering, with an exponential increase in its AOG times, resulted in an operational collapse: its cancellation rate soared to 7%.

At this point, the "potential loss" in the consumer's mind ceased to be a remote possibility and became a tangible probability. Flybondi had crossed the threshold where perceived risk outweighed the benefit of savings. JetSMART, with a modern fleet, proved more resilient under the same pressures, maintaining superior reliability and selling not just a ticket, but certainty.

The Market's Verdict: The "Battle of the Buts"

The market reaction was an empirical confirmation of Kahneman and Tversky's postulates. Consumers, acting under the influence of loss aversion, executed a mass migration.

Beyond the evident decrease in market share, one of the main assets that Argentina's first low-cost carrier lost is precisely that: being recognized as a synonym for LCC in the local market. Following the repeated operational issues, the focus of the discussion shifted, and a complex association began to gain ground in the company's perception. In conversations with industry insiders, the consensus defined a "battle of the buts": a ubiquitous and difficult enemy to fight.

Starting in 2021 (the first year of competition under similar conditions despite the post-pandemic scenario, as JetSMART consolidated by acquiring Norwegian Air Argentina in December 2019, and the COVID-19 crisis began just a quarter later), the two domestic low-cost carriers had similar levels of transported passengers and market share. At that time, price was a deciding factor in passenger preference.

Flybondi's advantage of having a lower-cost structure with cheaper leases and the intrinsic value of being the first Argentine low-cost carrier was evident. In any industry, even more so in the service industry, and still more in commercial aviation, it is very difficult to achieve "Top of Mind" status in a market. For years, Flybondi was Top of Mind, with no buts.

But when reliability started to become a factor, price ceased to be one. And so the low-cost airline market in Argentina was configured with two players: Flybondi, the cheap but unreliable option, and JetSMART, the more expensive option, but with less uncertainty.

In this peculiar Argentine market, where prices are absolutely relative due to the lack of a frame of reference, and with one company in Damage Control mode (Flybondi) and another making moves to maximize competitiveness and thus narrowing the price gap, the "buts" became more important.

And that's when, according to Kahneman and Tversky, a familiar song began to play. One that was very much in vogue in Nevada, back in the 2010s.

The Case of Allegiant Air

This phenomenon is not unique to Argentina. The reaction of the local market is an echo of the crisis suffered by Allegiant Air, and the parallels with Flybondi's situation, even with their differences in case specifics and chosen equipment, demonstrate the universality of the principle.

Allegiant faced a major reliability crisis with the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 fleet with which it began operations, which peaked between 2015 and 2018. A series of in-flight mechanical failures, emergency landings, and aborted takeoffs cast a shadow over the airline's safety record, leading to intense media scrutiny, federal investigations, and, ultimately, the complete retirement of the fleet. The crisis was characterized by a high frequency of mechanical incidents that raised concerns among both the public and regulatory authorities.

Attention on the problems was intensified by investigative reporting. A 2016 investigation by the Tampa Bay Times revealed that Allegiant's planes were four times more likely to experience in-flight failures than those of other major US airlines. The report detailed numerous cases of engine failures, smoke in the cabin, hydraulic leaks, and flight control malfunctions.

Amplifying these concerns, a "60 Minutes" report on CBS in 2018 highlighted more than 100 serious mechanical incidents between January 2016 and October 2017, featuring testimonies from former pilots and passengers who recounted harrowing experiences.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) also increased its oversight of Allegiant during this period. Although the agency did not ground the fleet, it publicly confirmed the higher number of incidents and its enhanced surveillance.

At the heart of the crisis was Allegiant's reliance on an older, second-hand fleet of MD-80 aircraft. While these planes were cheaper to acquire, they required more rigorous and costly maintenance. Critics argued that Allegiant's ultra-low-cost business model, focused on minimizing operating expenses, may have compromised its maintenance standards.

At that moment, Allegiant passengers faced the same psychological calculation: the "gain" of a low fare versus the "potential loss" magnified by uncertainty. Once the risk was perceived as real, Loss Aversion was activated en masse.

In response to the growing pressure, Allegiant's decision was to accelerate its fleet modernization plan. The airline, which had already begun to incorporate newer, more efficient Airbus A320 aircraft, fast-tracked the process due to the persistent problems with the MD-80s.

In November 2018, Allegiant officially retired its last Mad Dog, marking the end of an era and completing its transition to an all-Airbus fleet. This move was a key step in rebuilding public confidence and improving its operational reliability.

Allegiant's solution validates the theory: they were forced into a costly total fleet modernization to Airbus A319/A320s, also used but with a much lower average age. But, over time, the move allowed them to regain passenger trust, changing the narrative and steering it away from the discussion of safety and reliability.

Allegiant didn't just sell the "new" planes as a concept; its new product was the elimination of uncertainty. The result was a flight completion factor of over 99.5%, rebuilding its value proposition around the nullification of the fear of loss.

Today, Allegiant seems to have learned from the crisis: it already has plans in motion to retire its Airbus A319/A320s and migrate to a fleet of Boeing 737 MAXs in their -7 (if it's finally certified) and -8200 variants. The company knows it cannot afford a return to questions about its fleet and is playing it safe. To (re)build trust, even if it represents a multi-million dollar investment, it has little other choice.

The Incalculable Value of Trust

The case of Flybondi, analyzed through the lens of behavioral economics and reinforced by the precedent of Allegiant, is a definitive lesson. In a high-involvement purchase like travel, the psychology of risk will always triumph over a simple promise of a low price once a critical reliability threshold is breached.

The difficult conditions of the Argentine market make renewing that fleet complex without it involving a major investment, but the company seems to have begun taking steps in that direction. The regulatory opening that allowed it to incorporate aircraft under a wet-lease arrangement to meet seasonal demand is a tool that may prove correct, provided that the operating costs of those aircraft on an ACMI basis—a leasing modality experiencing extremely high demand— remain within reasonable margins.

The renewal and return to service of Flybondi's own fleet—that is, on dry-lease—has also begun to happen, and all signs indicate that its operations will continue to normalize in the coming months. It is too early to predict how much time and effort it will take to reverse public perception, but a few timid steps are still better than no steps at all.

The final product is not the seat on a plane; it is the predictable arrival. When that promise is systematically broken, the architecture of the human mind dictates that no amount of savings is enough to compensate for the fear of loss. It is in Flybondi's hands to regain passenger trust: It will not be easy. But (and this is a positive but) it is possible.

/https://aviacionlinecdn.eleco.com.ar/media/2024/02/flybondi-lv-kdr-aeroparque.jpg)

Para comentar, debés estar registradoPor favor, iniciá sesión